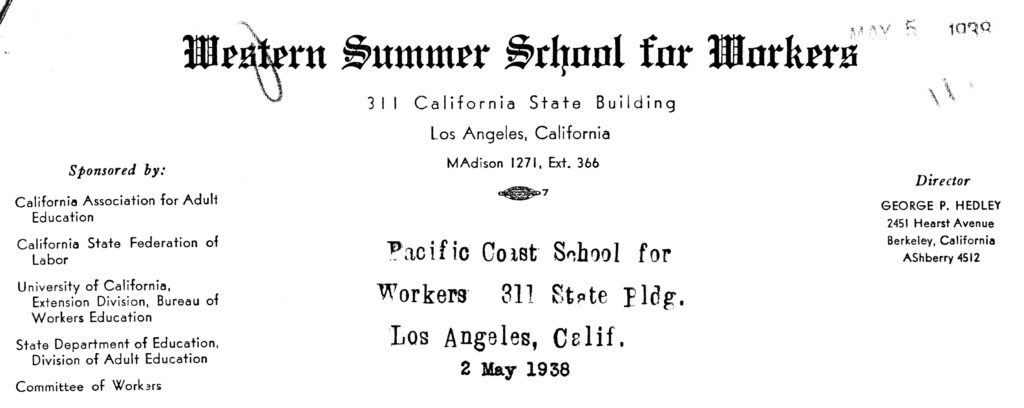

In the summer of 1933, California union organizers, state education officials, and the University of California Workers' Education program collaborated on the first Western Summer School for Industrial Workers. Later renamed the Pacific Coast Labor School, the Western Summer School was an important forerunner of the University of California Institute of Industrial Relations that was founded in 1945. This document from the school's archive at Occidental College Library names many of people and organizations that helped launch the program.

How to cite: "Class Record: Summer School for Industrial Workers, Occidental College, August 1933," Pacific Coast Labor School records, Occidental College Library.

Summer School for Industrial Workers

Occidental College

Los Angeles, California.

August 1933.

History

The Summer School for Industrial Workers which opened its doors at Occidental College on Sunday evenings, August 6, 1933, is the realization of a dream which originated several years ago with a club of Industrial Workers at the Young Womens Christian Association in Los Angeles. The Club was started in 1928 by Sadie Goodman, who had attended the first Workers Summer School at Bryn Mawr. It met weekly for study and discussion; and from among its members students were chosen each year for Bryn Mawr.

The group talked often of the possibilities of a Workers School on the Pacific Coast, and two years ago, under the inspiration of Helen Richter, Bessie Goren, and Sadie Goodman, it took the first active steps. Both Scripps College and Occidental College gave warm support to the project; and Occidental offered its hospitality for the summer of 1933. The California Association for Adult Education was invited to cooperate with the colleges, the Y.W.C.A., and other bodies, in organizing the School, and its Director, Mrs. Lucy Wilcox Adams, was placed in charge of the work.

The plan of the School was launched at a dinner at the Los Angeles Y.W.C..A. on March 13, 1933, at which Dr. Remsen D. Bird, president of Occidental College presided. Representatives of a number of colleges, clubs, and educational institutions were present and expressed their support of the project. A committee representing the various interests concerned in the founding of the School was appointed to perfect plans and raise the necessary funds. Mrs. Ethel Richardson Allen former chief of Adult Education in California, acted as chairman. Other members of the committee were:

Dr. John Darr of Scripps College, Mrs. Irene Heineman, Assistant State Superintendent of Public Instruction, Mirian Bonner, former instructor in the Bryn Mawr and Vineyard Shore

Schools for Yorkers, Mary Buchtel, Assistant Secretary of the Los Angeles Y.W.C.A., Florence Nichol, Industrial Secretary of the Los Angeles Y.W.C.A., Ethelwyn Mills, Anne Peterson of the International Ladies Garment Workers, Dr. W.A. Diebold of the Unemployed Cooperative Relief Association, Sadie Goodman, Bessie Goren and Helen Richter, representing the Industrial Club of the Y.W.C.A., Dr. William F. Adams of the

University of California at Los Angeles, and Mrs. Lucy Wilcox Adams of the California Association for Adult Education. This committee worked with a committee representing Occidental College under the chairmanship of Anne Munford, and received the most cordial and helpful cooperation.

The plan as finally agreed upon called for a four weeks school from August 6 to September 1, 1933 at Occidental College. Orr Hall, one of the womens’ dormitories, was placed

at the disposal of the students, and the fountain room of the College Union was opened for meals. The original intention had been to limit the students to women, but at the meeting in March the men present asked to have the privileges extended to men as well. This was agreed upon, but it was deemed advisable because of expense to limit residence to women. The sum of $25.00 per resident student for the four weeks period was set as the amount of the individual scholarships. This covered the cost of room and board, laundry, the services of the kitchen staff, and other incidental expenses. Dr. Bird offered to make himself responsible for the cost to the college of the School. In addition to the residence fee, a registration fee of $1.00 was charge.

Meanwhile, the Extension Division of the University of California was invited to participate in the School and accepted. Its Workers Education Bureau, representing jointly

the University and the California State Federation of Labor, assigned its Director, John L. Kerchen, to the School.

A second dinner under the chairmanship of Mrs. Lucy Wilcox Adams was held at the Y.M.C.A. in Los Angeles on May 8th. Completed plans for the school were announced, together with the proposed curriculum and the names of the Faculty. In view of the fact that the School was a new venture in the West, the Faculty all volunteered their services. Without this assistance it would have been too difficult, if not impossible, to raise the necessary funds. The outstanding event of this dinner was the presentation by the Industrial Club of the Y.W.C.A. of the first scholarship, and their example stirred the gathering present to raise another scholarship to match it.

A committee under the chairmanship of Mrs. Adams was appointed to prepare a bulletin of information and an application blank, and a scholarship committee under the chairmanship of Miss Ethelwyn Mills was formed to interview prospective students. The purpose of the School as outlined in the bulletin was as follows:

“The Summer School for Industrial Workers at Occidental College has been established to provide opportunity for workers in industry to study the social and economic problems of present day industrial society, to train themselves in clear thinking, and to develop a desire for study as a means of understanding and enjoyment or life. The Summer School is not committed to any dogma or theory, but will conduct its teaching in the spirit of impartial inquiry with freedom of discussion and instruction.”

The original intention had been to limit membership to applicants with at least three years of wage-earning experience, two of which, preferably, should heave been in industry;

but the rule was relaxed to some extent and a few men and women from the business field and the ranks of domestic workers were enrolled. A limited number of college students were also admitted to serve in the capacity of tutors and general assistants.

It did not prove an easy matter to raise funds in the midst of the general business depression, but the help of the following organizations and individuals made possible the

School: Occidental College, Pomona College, Scripps College, Stanford University, the University of California, the State Federation of Labor, the Los Angeles Y.W.C.A., the Industrial Club of the Los Angeles Y.W.C.A., the Pasadena Y.W.C.A., the San Francisco Y.W.C.A., the Womans Civic League of Pasadena, the Girls Council of Los Angeles, Mrs Ethel Richardson Allen, Miss Averic and Miss Elsie Allen, Dr. and Mrs. Remsen Bird, Miss Martha Chickering, Mrs. Oliver C. Field, Mrs. Ludwig Frank and a group of friends in San Francisco who raised a scholarship in memory of Mrs Jesse Steinhart, Miss Helen Marston, Miss Ethelwyn Mills, Dr. Ernest C. Moore, Dr. Gordon Watkins, Dr. C.H. Rieber, and Miss Mary Yest. Special thanks are due to Dr. John Darr of Scripps College for his continued help in every phase of the School’s activity.

It has been possible to carry on the School on the meagre budget of $700 partly through the assistance of the students, all of whom have worked in the dining room, and have been responsible for the care of their own rooms, and for some measure of janitor service. This has proven very satisfactory, and has reduced service charges to a minimum.

The work of interesting students in the School was accomplished largely through the efforts of the Industrial Club of the Y.W.C.A. and by meetings at the Labor Temple and

at various unions. At the last moment plans were upset to some extent as the adoption of NRA gave jobs to half a dozen or more prospective students. But on August 6, 1933, a total of 29 students were enrolled and attended the Opening Exercises.