A clipping of a 1990 article describing a Justice for Janitors training held in from of the Los Angeles Police Department. Janitors were preparing to use non-violent civil disobedience in their strike on Bradford Building Services in November of that year. Translated from Spanish by Juan Torres.

“Cleaning workers to go on strike” La Opinion, October 19, 1990

By Miguel Molina

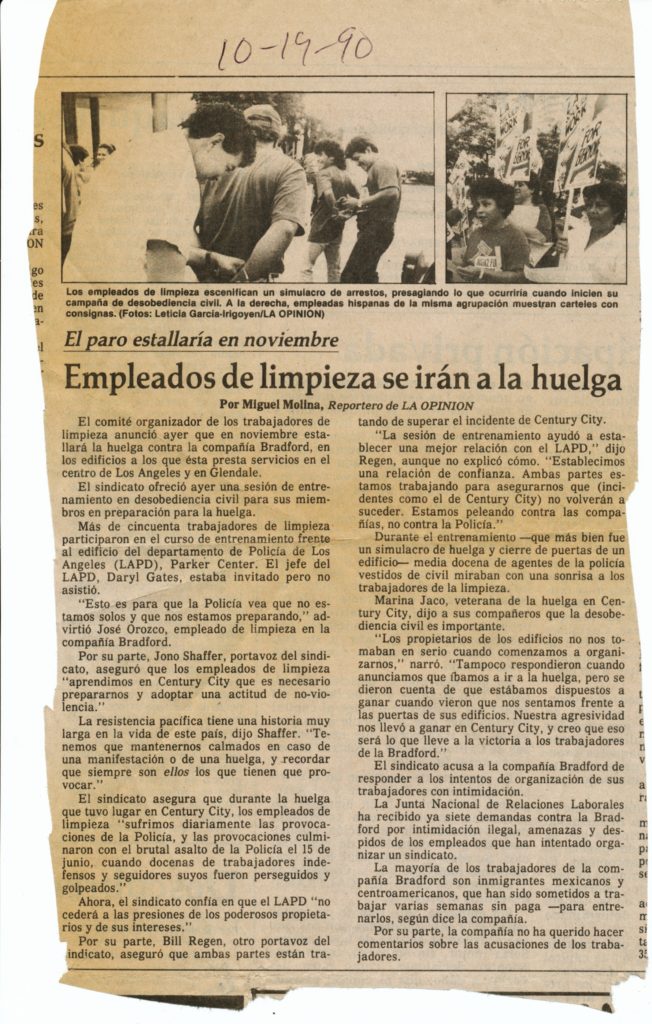

Image caption: Janitors stage an arrest drill to prepare for what will occur as a result of their civil disobedience campaign. To the right, Hispanic women janitors from the same group show signs with slogans. (Picture by Leticia García-Irigoyen/ La Opinion)

Yesterday the committee that organizes cleaning workers announced that on November a strike against the Bradford Company in the buildings in which they provide their service located in the center of Los Angeles and in Glendale.

The union offered courses of civil disobedience to its members in preparation for the strike.

More than 50 cleaning workers participated in this course in front Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) building, located in Parker Center. LAPD Chief, Daryl Gates, was invited to the training but he did not attend.

“This it to show the police that we are not alone and that we are preparing,” warned Jose Orozco, janitor in the campaign against Bradford.

Jono Shaffer, spokesman for the union, assured that the janitors “in Century City learned that it is necessary to prepare ourselves and adopt an attitude of non-violence.”

Peaceful resistance has a long history in this country, said Shaffer. “We have to keep calm in a demonstration or strike and always remember that they are the ones who have to provoke.”

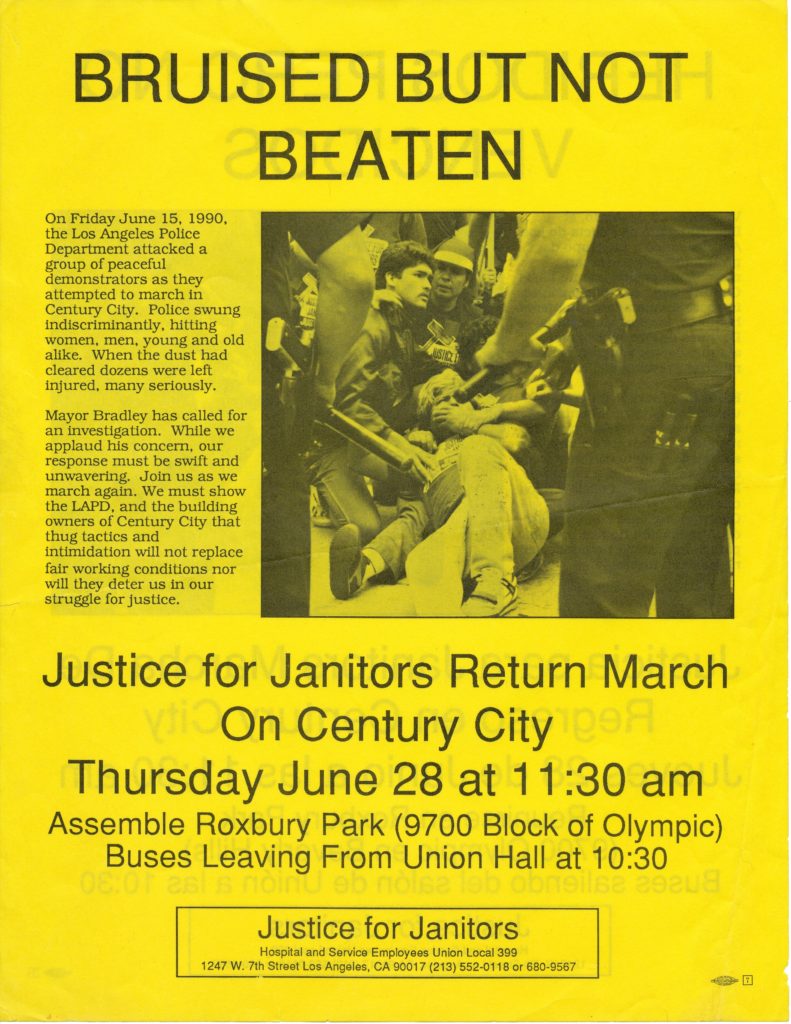

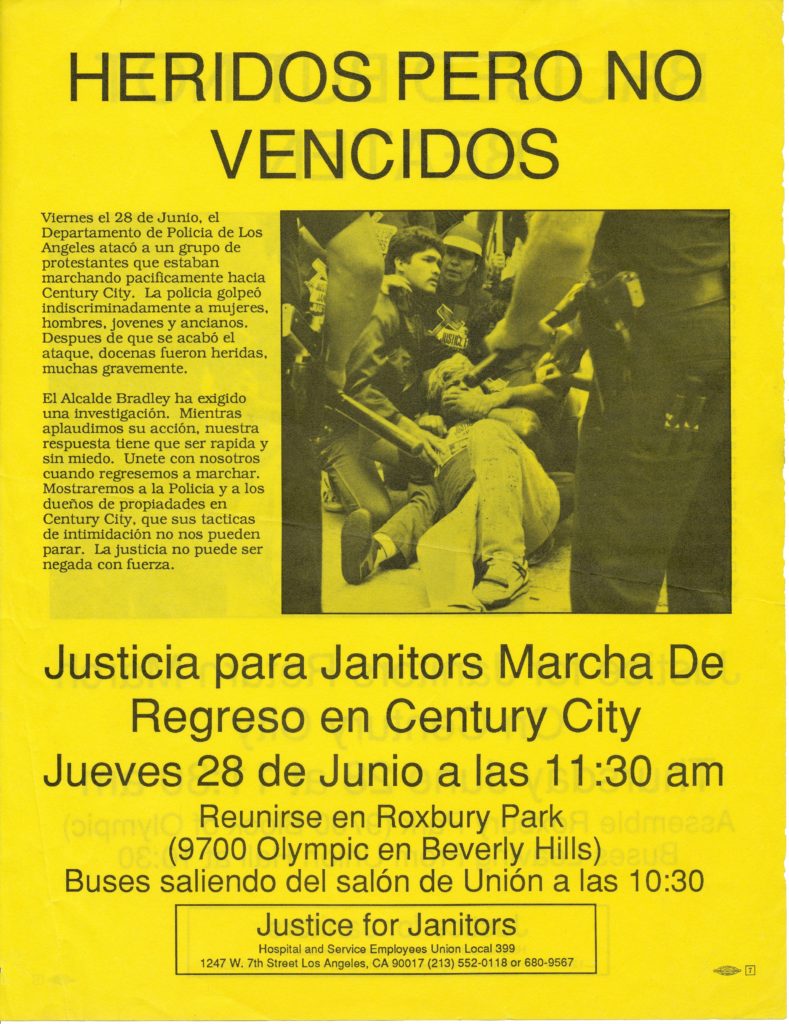

The union assures that during the strike in Century City “we suffered daily provocations by the police that culminated in the police assault on June 15, when dozens of janitors and supporters were chased and beaten.”

The union believes that now LAPD “will not consent to the pressures of the powerful proprietors and their interest.”

Another spokesman for the union, Bill Regen, assures that both parties are trying to overcome the Century City incident.

“The training course helped established a better relationship with LAPD,” said Regen, although he did not explained how. “We established a relationship of trust. Both parties are working to assure that (incidents like the one that occurred in Century City) will not occur again. We are fighting against the corporations, not against the police.”

During the civil disobedience training–which realistically was more of a strike and shut down of the building’s doors training– half a dozen plain clothes police looked on with a smile at the janitors.

Marina Jaco, a Century City strike veteran, said to her janitor partners that civil disobedience is important.

“The owners of the building did not take us seriously when we started to organize,” Jaco said. “They also did not respond when we announced we were going on strike, but they realize that we were willing to win when they saw us sitting outside the doors of their building. Our aggressiveness allows us to succeed on the Century City strike, and I think this will carry to victory in the campaign against Bradford.”

The union accuses Bradford Company for intimidating any efforts to organize workers into a union.

The National Labor Relations Board has received seven complains against Bradford’s illegal intimidation practices, threats, and lay off of workers who have attempted to organize a union.

Most of the workers from Bradford Company are immigrants from Mexico and Central American, who have been compelled to work without pay for weeks, supposedly to train them.

Bradford did not comment on the workers the accusations.