In September 2006, UNITE HERE Local 11 organized what was likely the largest act of civil disobedience in Los Angeles History. Union members, faith leaders, elected officials, and community allies joined in a large march to protest low wages at corporate hotels along Century Blvd outside of Los Angeles International Airport. The protest demonstrated the union’s ability to build a broad coalition in support of worker and immigrant right at a time when the union was negotiating with hotel employers over a new contract. Building on the themes of the spring 2006 immigrant rights marches, Century Blvd. marchers also evoked the civil rights movement. The slogan “I am a Human Being” echoed the famous message Memphis sanitation workers strikers of 1968, “I am a Man.” Over 300 demonstrators were arrested by Los Angeles Police and bused to Van Nuys for processing. Produced by UNITE-HERE Local 11, this film combines TV news footage, interviews, and street scenes to document the union’s mass action on Century Blvd.

Los Angeles Immigrant Rights March, 2006

On May 1, 2006 hundreds of thousands marched in Los Angeles and other large U.S. cities in support of immigrant rights. Called by many “A Day without an Immigrant,” the May Day protests were the culmination of months of planning in response to a punitive immigration bill that passed the U.S. House of Representatives (H.R. 4437). This video is from the Los Angeles Independent Media Center (IMC, http://la.indymedia.org/news/2006/05/156112.php). Independent media in LA and elsewhere was an important venue for social movement news in the early 2000s, but in Los Angeles the large crowds were also mobilized by Spanish-language commercial radio and television stations that embraced the call to oppose H.R. 4437.

“Our major responsibility and task”: Kent Wong and the 2000 DNC in Los Angeles

The IRLE and labor communities in Los Angeles are mourning the loss of Kent Wong, an outspoken champion of worker rights and labor education. Kent was a tenacious advocate for the most vulnerable, a creative strategist, and an inspiring teacher and mentor to so many. You can read the IRLE’s full statement on his passing here. To honor Kent’s many contributions to the workers justice movement, we will be featuring moments from his life over the coming months, beginning with this interview at the 2000 Democratic National Convention.

In August 2000, the Democratic National Committee held their convention at the Staples Center in downtown Los Angeles. The convention came amidst grassroots insurgency and popular discontent with the Clinton-era model of neoliberal governance at home and abroad. In November 1999, labor unions, environmentalists, faith leaders, and students mobilized in Seattle at the World Trade Organization meeting to protest the new global regime of “free trade” that the Clinton administration helped to enact. Their often confrontational tactics were met by a ferocious law enforcement response that culminated in the Governor of Washington sending in the National Guard to impose a “no protest zone.” The so-called Battle of Seattle inspired similar anti-globalization demonstrations against the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund in Prague and Washington D.C. in the months that followed.

Tensions were also high in Los Angeles in the summer of 2000. Just a few months earlier, the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) made headlines with a major corruption scandal centered at its Rampart Division, where officers were revealed to have been involved in shootings, bank robberies, and drug thefts. In early June, the Justice for Janitors campaign of SEIU had waged a successful two-week strike that featured dramatic street demonstrations, at one point threatening to picket outside the NBA Championship at Staples Center. In preparation for the arrival of Democratic Party delegates, the LAPD announced it would be increasing surveillance and enforcement downtown, including establishing a special fenced-in “Media Zone” for the press and “free speech zone” for protesters in a parking lot across from the Staples Center.

The spirit of anger, rebellion, and defiance at the convention – engendered by both the LAPD and the Democratic Party – found an outlet on the first night of the convention when, as President Bill Clinton addressed the convention inside, Rage Against the Machine performed in the “free speech zone.” It also took another form: an independent media group, along with left-leaning journalists and activists, organized a so-called Shadow Convention at the nearby Patriotic Hall. Among them was Kent Wong, the director of the UCLA Labor Center, who was interviewed there by a student activist about his perspective on the DNC and the labor movement. An un-edited video of the interview appears in the IRLE video collection, however the sound quality of the ten-minute video is poor, making it difficult to hear the questions being asked by the reporter as well as Wong’s responses. For that reason, we’ve offered a slightly-edited transcript of the interview below. As we hope you’ll see, Kent speaks with the same vision and clarity that guided his career as an educator, scholar, and organizer.

Kent Wong, interviewed at the “Shadow Convention” during the DNC, August 2000. Wong was asked to begin by introducing himself:

“I’m Kent Wong, I’m the Director of the UCLA Labor Center. We’re very excited to be here as part of the shadow convention and to see all the incredible energy here in the streets of Los Angeles around the Democratic National Convention. I think that this is a very historic time for our movement for social and economic justice, and I see potential for tremendous convergence between labor unions, human rights activists, environmentalists, community-based organizations that has not happened in a long, long time. So, I think that this is really where the future and the hope lies. There’s a lot of debate with regard to the November elections and who we should be supporting, what type of work we should be doing. I really think that the crucial thing for us in this period of time is to strengthen grassroots organizing, grassroots mobilization, and base building. What we’ve seen here in Los Angeles in the last few years is a dramatic resurgence in the Los Angeles labor movement. Immigrant workers are doing unprecedented work in building unions in workforces that have not been unionized in decades and there is this new energy and hope and spirit that, as a consequence, they are bringing into the labor movement. There have been 90,000 new workers brought into the Los Angeles labor movement last year alone. And there is more opportunity—we’ve seen that in the streets of Seattle with the WTO demonstration, in Washington D.C. against the World Bank and the IMF, and right here in Los Angeles and in Philadelphia – the outrage about the corporatization of the political process, about the global domination of capital, and how increasingly working people’s interests and communities of color, poor people are not being heard in this midst of this election.”

He was then asked to comment on the relationship between anti-globalization activism and the labor movement and the impacts of “free trade” in Los Angeles:

“There is unevenness within the American labor movement and there are certain unions that are really at the forefront of building strong organizing campaigns and bringing women, immigrants, people of color into the ranks of the American labor movement. And here in Los Angeles, the Service Employees International Union, the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees union, are among the leaders of this movement to organize the unorganized, to bring more diverse people into the labor movement. The reality is that, in terms of the pressures of global capital, it’s the manufacturing unions that are really hurting. They’ve experienced tremendous capital flight, plant shutdowns, the numbers in the manufacturing unions have shrunken substantially in the last few decades. And yet, here in Los Angeles, we have the largest concentration of manufacturing workers in the country. There are close to 700,000 manufacturing workers and the majority are low wage, people of color, immigrants. The largest concentration is the 120,000 garment workers, mainly immigrant women, and the vast majority of those workers don’t even make minimum wage. So [these are] the conditions that we face here in Los Angeles. What I think has emerged very clearly in the midst of some of the exciting organizing that is going on, is that unions realize that they can’t take this challenge on alone and that it’s going to be crucial for battles now and battle in the future to forge very strong partnerships between labor, community allies, the church, environmentalists, human rights, women’s rights groups. And that is the type of convergence that I think we’re seeing here in Los Angeles, in Seattle and in Washington D.C.”

Wong was then asked about the specific impacts of “free trade” on the garment industry and whether existing labor law can truly protect garment workers:

“We really need to explore new forms of organization. The reality is that the vast majority of garment workers are not in unions, but the vast majority of garment workers if given the option, if given the right to join unions, they would do so. If given the right to have a contract, have a living wage, have healthcare benefits, have on the job protections, they would do so. When UNITE, the garment workers union, has tried to organize workers in the garment industry, they have been met with fierce opposition, brutal suppression where, when they successfully organize a Guess [Guess? Jeans] plant, Guess shuts down the factory [and] moves to Mexico. And this sends a chilling message within the garment industry that even if you dare to take the risk and stand forward and to organize, you are confronted with that type of repression. That you’ll lose your job, you’ll be…you know, the factory will shut down. So that is the message that major corporations are sending. We need to explore new forms of organization and that can only happen through a comprehensive dialog between unions, community allies, the religious community, and so forth. And we need to find new ways of bringing workers who very much need the protections of unions into the labor movement.”

Finally, Kent is asked to comment on the DNC and the candidacy of Al Gore:

“The American labor movement came out with an early endorsement of Al Gore that took place in the October 1999 AFL-CIO national convention that was held right here in Los Angeles. That was a pragmatic decision. The decision of the American labor movement was that between Al Gore and George Bush, that Al Gore would provide a much better chance for unions in this period ahead. That he would allow some level of breathing space, that he would allow some level of support for some of the initiatives that labor is engaged in. I don’t think there’s any illusions that Gore represents the hopes and aspirations of working people. Income disparity has grown in eight years of the Clinton-Gore administration. The ranks of the poor has grown, the number of people without healthcare insurance has grown under the Clinton and Gore administration. And yet if you look at the alternative of George Bush, you see a very frightening prospect indeed, with his stance on abortion, on worker rights, on human rights. It’s a deplorable track record with regard to what George Bush represents. So, in building political power, we are going to have to develop a much stronger national movement for social and economic justice to push the national leadership. And what we see in the course of political mobilization, is that more working families and working people are getting mobilized in the course of political action. And you see changes going on in the demographics, you see changes going on in city councils and in the state house. And you see, in the state of California that, yes it’s true that Gray Davis doesn’t agree with labor on a lot of issues, but there’s been a major sea change. There is a difference between Pete Wilson and Gray Davis, there is a difference between having a democratically-controlled state legislature and a right-wing republican—you know pro-226, pro-187, anti-worker, anti-immigrant, anti-women’s rights, anti-gay and lesbian issues. So, there’s a difference and I think that we can’t belittle the difference that exists. That does not challenge our major responsibility and task: and that is to build a broad-based movement for social and economic justice that can push for much more fundamental change that we desperately need in this country.”

We call each other sister unions

Rocio Sáenz recalls the spirit of solidarity among unions in the early 1990s

I come from Mexico City, and I had a union there. Even though, looking back at the unions in Mexico, they were often very corrupt, at the time I thought it was better than nothing. When I came to the U.S., I did a lot of different jobs. I was a domestic worker, I was a salesperson in a store, and stuff like that. But I wanted to be in a unionized workplace, and so I was trying to get a job through a local union. I didn’t know that there was such a thing as being an organizer, but I was making posters and banners for he ILGWU. A few months later, I met someone in Local 11 of HERE and they hired me. Even then, for a few months, I didn’t do organizing. I didn’t even know what it was. But then I got very involved.

I saw a different way to organize [in HERE]. To bring the trust back from the members, and to show that this was a different union. In any organizing drive, you have to show the workers that, yes, you can make a difference. Little victories that you have to deliver, in order to say there is a change. It has to be very, very specific and concrete. And you have to see things as industry-wide. When I was with HERE I remember organizing my first hotel, reorganizing it for the first time in then years. That was in Manhattan Beach, close to the airport. We did it through elections. Well we organized 300 workers, and that was not going to make a big difference for the industry. You have to look at the whole industry, instead of one single work site. You have to do it in a market competitive way. If you’re going to organize, it has to be like all of downtown L.A. has got to go union. It has to be a long-term plan It takes a lot of effort, a lot of persistence, and a lot of resources.

“You’ve got to keep the heat on in different ways, and you’ve got to be very unpredictable

— Rocio Sáenz

We were the union they’d call

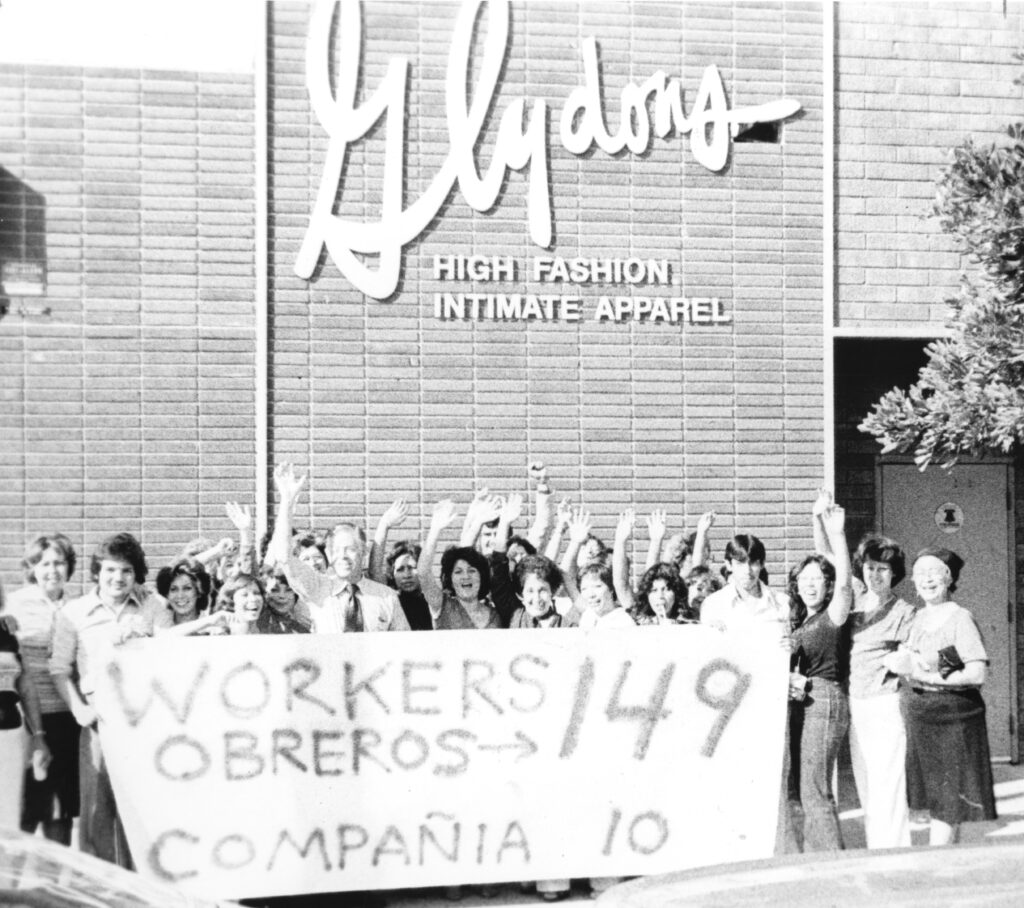

Cristina Vázquez on the lessons of organizing immigrant workers in the 1970s

In 1976, when I started working for the ILGWU, we had several thousand members, but for ten years they had hardly organized a shop. The union had not paid much attention to the situation in L.A. … but then the ILGWU decided to bring an organizing director from back east, Phil Russo. He was an organizer himself and he had a vision. He thought there was a lot of potential here, and he said he was going to find and hire the best organizers. He started going to the universities and recruiting people who were active in political groups. He put a team together, and among them was my husband, Mario F. Vázquez, who had just graduated from UCLA law school after emigrating from Mexico at age 15. He saw this ad, “Organizers Needed at ILGWU.” At the time he was doing some volunteer work for CASA (Centro de Acción Social Autónomo), the Chicano pro-immigrant organization, writing and translating for its newspaper, Sin Fronteras [Without Borders], and doing all this political work.

“This union was in front of the fight against employer abuses in the immigrant community”

–Cristina Vázquez