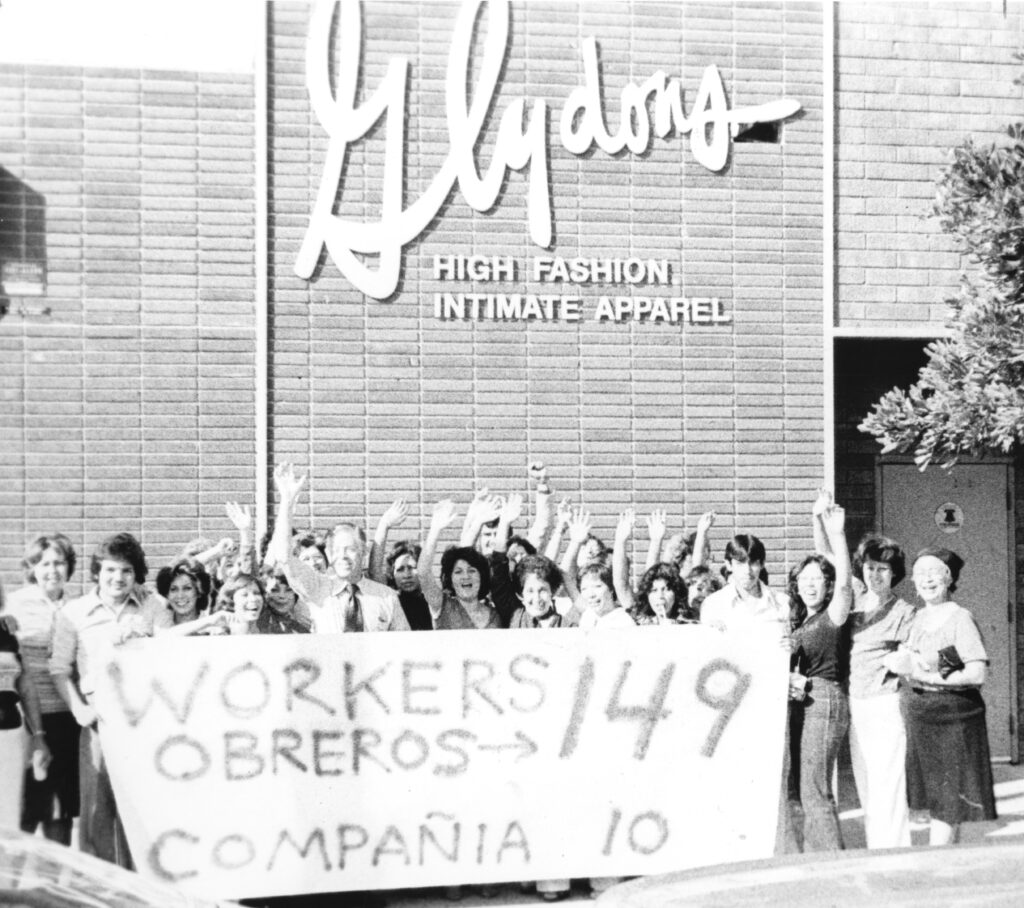

The Multi-Ethnic Immigrant Workers Organizing Network (MIWON) formed in the year 2000 to support immigrant and undocumented immigrant labor rights across Los Angeles. The coalition brought together the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights (CHIRLA), Instituto de Educación Popular del Sur de California (Institute for Popular Education of Southern California, IDEPSCA), Koreatown Immigrant Workers Alliance (KIWA), the Pilipino Worker Center (PWC), and later the Garment Worker Center (GWC), among other organizations. Throughout its ten years, these groups committed themselves “to the struggle for dignity, justice, and the human rights of immigrant workers and all peoples,” through sharing strategies and information, fostering interethnic and interracial solidarity, and promoting political consciousness and civic engagement among low-wage workers in Los Angeles.

MIWON campaigned for the passage of the “Immigrant Workers Bill of Human Rights” at the Los Angeles City Council in 2001, and to expand undocumented immigrants’ access to drivers’ licenses and government-issued identification. But perhaps their most enduring tactic was their annual commemoration of May Day (International Workers Day), marches that promoted solidarity among multiethnic and immigrant workers in Los Angeles and beyond.

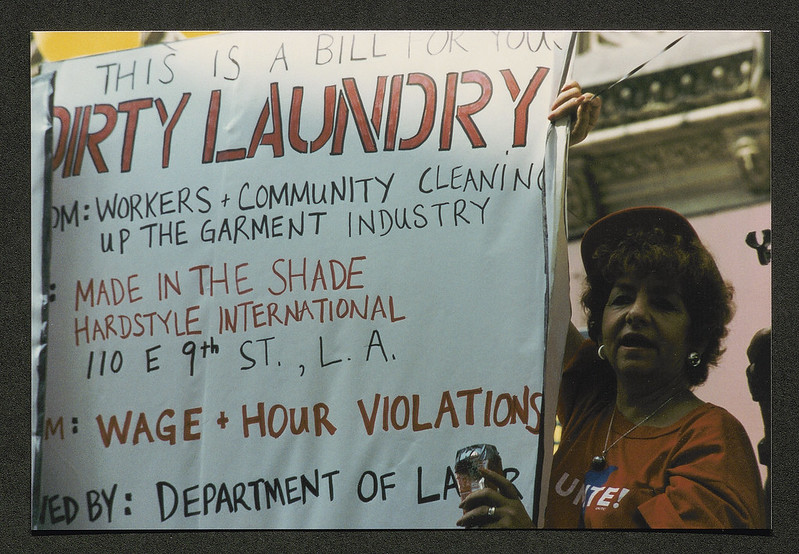

Pictured here: a scene from MIWON’s May Day march in 2003, where protestors connected “immigrant bashing” in Los Angeles and the United States government’s invasion of Iraq weeks earlier.

View more images from the 2003 May Day march here.