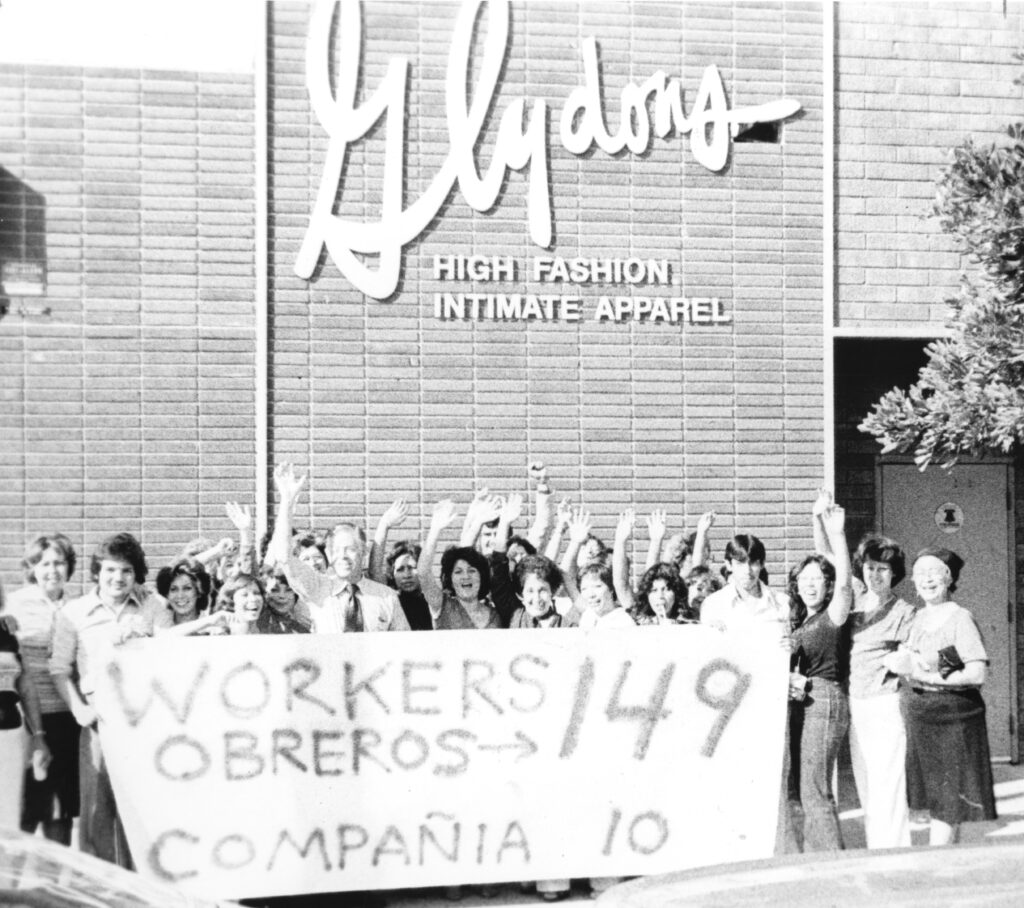

Cristina Vázquez on the lessons of organizing immigrant workers in the 1970s

In 1976, when I started working for the ILGWU, we had several thousand members, but for ten years they had hardly organized a shop. The union had not paid much attention to the situation in L.A. … but then the ILGWU decided to bring an organizing director from back east, Phil Russo. He was an organizer himself and he had a vision. He thought there was a lot of potential here, and he said he was going to find and hire the best organizers. He started going to the universities and recruiting people who were active in political groups. He put a team together, and among them was my husband, Mario F. Vázquez, who had just graduated from UCLA law school after emigrating from Mexico at age 15. He saw this ad, “Organizers Needed at ILGWU.” At the time he was doing some volunteer work for CASA (Centro de Acción Social Autónomo), the Chicano pro-immigrant organization, writing and translating for its newspaper, Sin Fronteras [Without Borders], and doing all this political work.

“This union was in front of the fight against employer abuses in the immigrant community”

–Cristina Vázquez

Mario started with the union in ’75, and I was hired in ’76…. At that time there were all kinds of problems organizing Latino immigrant workers. Nobody else wanted to organize them. Hardly anyone thought it was possible. The County Federation of Labor at the time was busy blaming immigrants for the decline of unions and for falling wages. No other union that I know of was organizing immigrant workers. It was only us. This union was in the front of the fight against employer abuses in the immigrant community. A lot of people saw us as the one union that organized immigrant workers, and we would get calls or referrals from workers about potential hot spots. We were the union they’d call, and we would try to go and organize. We were able to get the union to file a lawsuit against the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) in protest of workplace raids in the L.A. garment industry. We were leading a lot of the fights against the INS.

So that was the beginning, when we were showing everybody else that you could organize immigrant workers. In one particular year, I think it was 1978, we had three strikes running at the same time. We won an election and a union contract at a furniture company in East L.A. by a vote of 100 to 0. We couldn’t get a contract so we went on strike. We had another strike in Vernon, in a place that made silk screened T-shirts, and still another one in Culver City, at a muffler factory. That was the second contract of the three elections that we won, and in fact that muffler plant is still under contract with us right now.

We had this wonderful organizing team in those days, but one error was that we were not focused. There was no strategic plan. We were just beating the bushes to see who would come out. There were plenty of shops with low wage work, the worst conditions, and all employing immigrant workers. But we were building a union of immigrant workers more than a garment workers union. I think it was a mistake, in retrospect, that we didn’t really concentrate on the garment industry.

From Ruth Milkman and Kent Wong, eds., Voices from the Front Lines: Organizing Immigrant Workers in Los Angeles (UCLA Center for Labor Research and Education, 2000), 3-10.