by Christina E. Springer

The City of Angels was booming in the 1980s. Los Angeles overtook Chicago as the nation’s second largest city, but not everyone benefited from this growth. Bankers, lawyers, and businessmen made comfortable salaries in the new high-rise office towers during the day, then returned to the suburbs where they basked in the luxury of the entertainment capital of the world. At night janitors scrubbed bathrooms, vacuumed carpets, and lugged trash down to the bottom floors of the same buildings. As the sun rose and suburbanites climbed into their cars to pour back into the city, the exhausted janitors rushed to finish cleaning so they could head to their second jobs. Underpaid and overworked they saw Los Angeles for what it really was: glamour by day, but a sweatshop by night.

Janitorial work had not always been like this. After World War II, the Building Service Employees International Union (they later dropped the “B” to become the SEIU) Local 399 established a strong presence in Los Angeles. As financial firms asserted more control over building owners, pressures to drive costs down led to the spread of non-union contractors and wages plummeted during the 1980s. As experienced janitors moved jobs to stay in the shrinking union sector downtown, contractors eagerly recruited new immigrant workers at lower wages. Local 399 began to research new approaches to win just pay, benefits, and better conditions for the new immigrant workforce. In 1985, SEIU created the Justice for Janitors campaign in response to the new problems the union was experiencing with the exploitative work arrangements of the non-union contract cleaning industry. The campaign’s model had been widely praised for its innovation, success, and flexibility. In 1987, Justice for Janitors was initially assigned to Local 399, the Los Angeles branch of SEIU, with a small pilot team consisting of two organizers, a servicing representative, and a researcher. The team worked to research the LA-specific intricacies of the building services industry. Understanding the structure of the industry was essential to the success of the campaign.

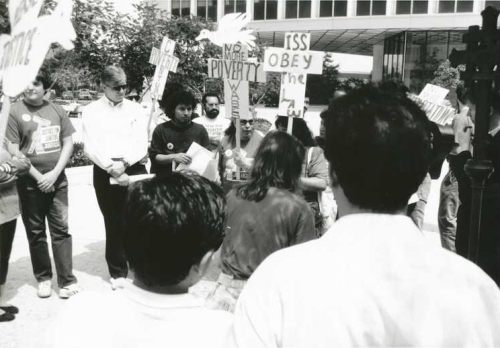

The Justice for Janitors campaign approached the Century City campaign as an “organizational laboratory,” developing new tactics and conducting critical research while establishing committees among the workers and useful connections with local media and government agencies such as the California Occupational Safety and Health Board and the National Labor Relations Board. Justice for Janitors also began to build relationships with local community groups, such as churches and neighborhood associations – especially those involved with the growing immigrant Latino population. Local 399 learned relatively quickly that the key to re-unionizing Los Angeles was to focus on all janitors in a specific area. In Century City, the Janitors movement focused on buildings managed by International Service Systems (ISS), at the time the largest multi-national building service and cleaning company in the world. ISS had contracts to clean eleven of thirteen office buildings in the neighborhood, all of which were owned by JMB Realty.

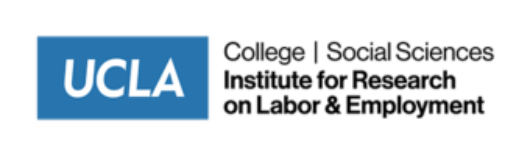

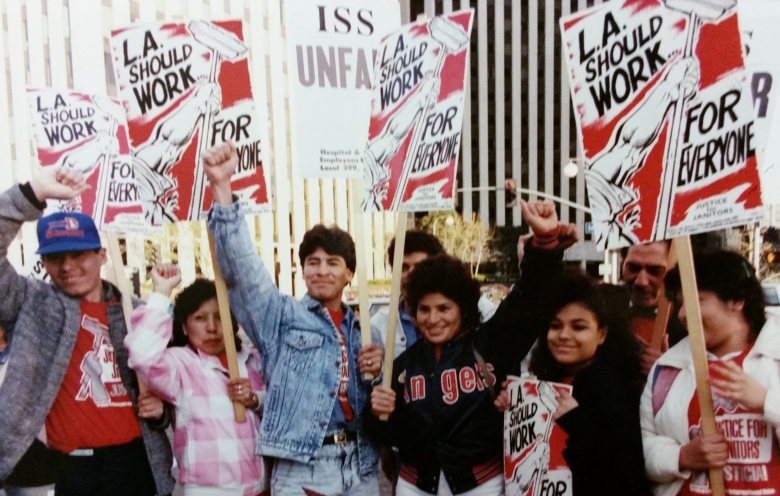

One of the union’s strongest and most frequently used actions in Century City was to declare strikes based on unfair labor practices, temporarily halting the cleaning of the buildings. Then the workers raised hell, making it difficult to conduct business as usual with the added complications of lawsuits, distractions, and public dramas. Janitors started small in this project with a series of one day walkouts that built their movement’s strength, and workers’ courage. The strikers and large groups of community supporters held rallies, sit-ins, and marches almost daily at the target buildings. They distributed flyers denouncing the contractors or building owners and raised awareness of the plight of the janitors to passerby. Meanwhile, Local 399 officials held countless meetings with building managers and crew supervisors to demand better conditions for workers.

During each strike, the campaign organized public dramas intended to increase awareness of the movement, pressure select individuals in the industry, and build public support. They began by demonstrating along Santa Monica and Olympic Boulevards with signs reading “Century City: Luxury by Day, Sweatshop by Night,” and “ISS + JMB Equals Poverty for Janitors.” In one particularly creative action, the union marched through the city and encouraged supporters to bring their garbage and dump it at Century City; later, in a nation-wide campaign, supporters mailed trash directly to the building owners.

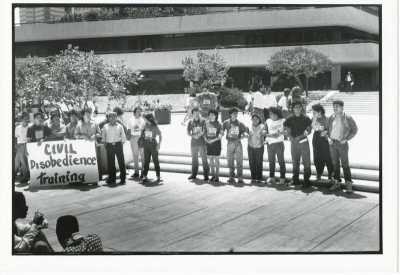

As the strikers grew in number and their supporters became more vocal, police presence at the public events increased. The Los Angeles Police Department eventually set up a command post in Century City, one of the safest neighborhoods in Los Angeles. In response, Local 399 conducted frequent civil disobedience training to ensure that the strikers were educated about their right to peaceful assembly and the legalities associated with protesting. This training prepared the demonstrators to submit to arrest and respond non-violently to provocation by the police, in anticipation of resistance from law enforcement.

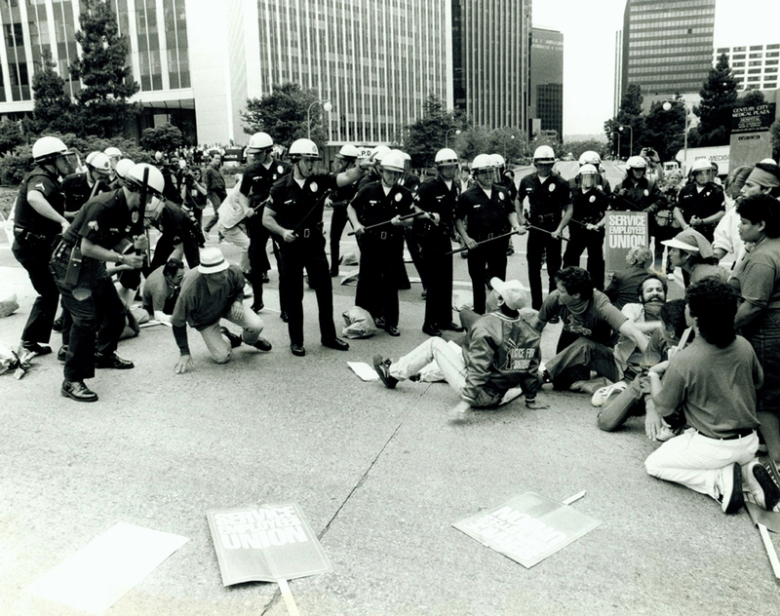

On June 15th, 1990, janitors marched from Roxbury Park in Beverly Hills to a planned rally in Century City. The peaceful protesters, clad in red Justice for Janitors t-shirts, were met by over one hundred members of the LAPD in full riot gear as they attempted to cross into the Century City office park. Though the marchers were in a public space, the police aggressively ordered them disperse. A bullhorn rang out, claiming the march was an illegal assembly. In an act of planned and non-violent civil disobedience, the protesters moved into the street and sat down, preparing to be arrested. Among them was Ana Veliz, an ISS janitor from El Salvador who made $4.25 an hour and worked two jobs to send money back to her mother and six children outside the United States. Veliz became pregnant in March of 1990 and fought with Justice for Janitors for the fair wages and health insurance she would need to safely deliver and raise her child.

Amidst the chaos, protesters were pushed from the sidewalks into the middle of the street. Police gave the protesters a thirty-second warning to disperse. In protest of the police action, some janitors and their supporters stayed on the street while others linked arms and attempted to submit to arrest. The police charged and struck protesters, indiscriminately beating women, men, children, and the elderly. They swung their batons, driving the front ranks of picketers back, causing those who were hit to stumble and fall over the bodies of marchers who were not able to scramble away. Pregnant Ana Veliz was clubbed three times in the back.

Twenty-one janitors were hospitalized and forty-two were arrested, including Veliz. She cried in pain and began to vomit. Four days later, a physician told her she had miscarried. The protesters were bewildered, shocked that the situation had become violent so quickly. The police conduct on the June 15th strike was widely criticized and spurred incredible public support from the people of Los Angeles and Mayor Tom Bradley, who ordered a full investigation into police conduct during the riot and invited representatives from Local 399 and the LAPD into his office. Bradley stood beside protesters a week later at Roxbury Park and urged ISS to negotiate a fair contract with the janitors. Local 399 filed a multi-million dollar lawsuit against the LAPD on behalf of the injured janitors.

The violence in Century City gave the Janitor’s movement unprecedented public visibility and organizing leverage. Within two weeks, ISS signed Local 399’s Master Building Service Agreement, leaving only three non-union buildings in the Century City office complex. The new agreement gave all ISS workers in Southern California an immediate raise to $5.20 per hour, and promised that another raise to $5.50 per hour along with health insurance would take place within a year. SEIU Local 399’s incredible success inspired janitors across Los Angeles and the United States to mobilize. When the campaign began in 1987, Los Angeles janitorial contractors were only 17% union and 83% non-union. By 1995, 81% of contractors were unionized. Although the national economy slid into recession in the early 1990s, janitors were protected by their new contracts. After Century City, the union moved on to other regions of LA, shattering the invisibility of building service workers across the city.

Christina E. Springer holds a B.A. in Political Science from UCLA.