In this excerpt of a 1995 speech on multi-union organizing strategy, David Sickler recounts the changing relationship between immigrant workers and organized labor in southern California and identifies some of the mistakes unions have made in their approach to immigrant workers. As the Regional Director for the AFL-CIO and head of the Los Angeles-Orange County Organizing Committee (LAOCOC), Sickler launched the California Immigrant Workers Association (CIWA) to organize undocumented workers into unions. This speech was delivered at the UCLA Labor Center.

Now I’m somebody who’s tried to organize immigrant workers in this town for 20 years. We’ve had some success here and there, but the movement’s never been able to prove to immigrant workers that it could deliver. That it could put its money where its mouth was.

Immigrant workers have always agreed with us philosophically. They know we’re advocates; they know we’re on their side. But they’ve been reluctant to get on board with us on a large scale because they’ve watched our failures. They know that some of our own unions in the past, when they’d go out and organize companies that had immigrant workers, if those workers went on strike and the employer replaced them with other immigrant workers, the union would call the INS and have the scab workers deported. The employer would then call the INS and have the strikers deported. That’s a great deal for immigrant workers. Welcome! Welcome to the institutions of the United States. But the labor movement changed its act in the 70s and the 80s, and we aren’t doing those kinds of things any more. Still, these workers just weren’t sure we could deliver. What happened with the signing of the Justice for Janitors contract sent shockwaves through the immigrant community in Southern California. It will never be the same, ever. Because about six months after the signing of that contract, 900 workers at American Racing Equipment in Rancho Domingas-and I’m telling you it’s 100 percent immigrant-staged a five-day walkout.

Now, I’m an organizer. I’m gonna tell you, 900 workers do not spontaneously walk out of a plant. There’s some leadership in there somewhere. There’s some organizing going on. You hear about hot-shop organizing? This was a super, super red-hot shop. These people organized themselves. And, of course, this is a classic example of how we as a movement respond. The day after 900 workers at American Racing Equipment go out on the street in a wildcat by themselves, 97 unions are out there with their jackets and their leaflets. “Join us; I’m with the Office Workers!” “Join us; I’m with CWA!” “Join us; I’m with the Steel workers!” “Join us; I’m with the IUE!” “Join us; we’re with UAW!”

“People wanted to change things so bad they organized themselves and went into the street.”

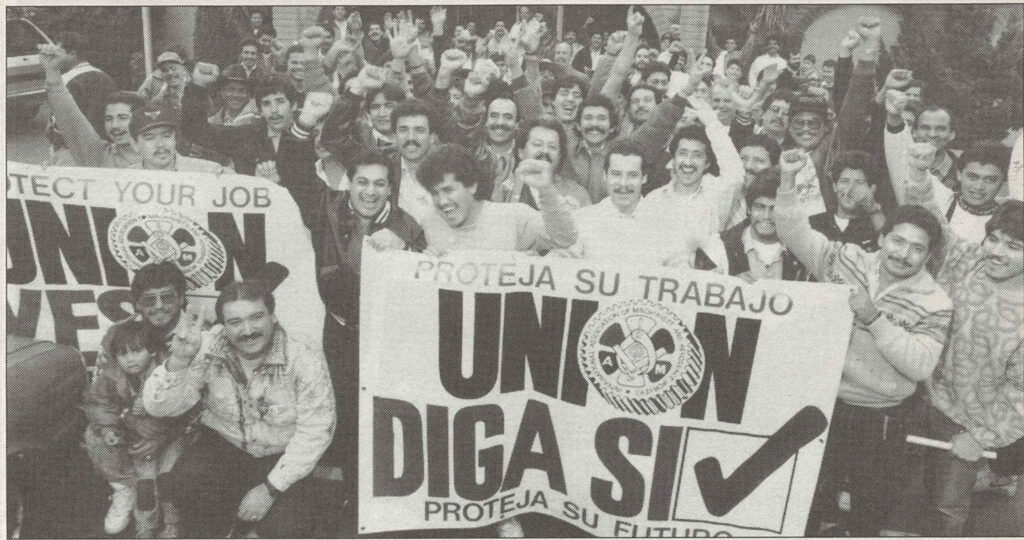

Well this is one of the roles that the Los Angeles-Orange County Organizing Committee (LAOCOC) played. We pulled all the unions together and said, “Stop this nonsense. You’ll scare these workers off. They’re gonna think you’re all nuts. Let’s sit down and talk about one union that has the best shot at organizing these people.” After several weeks the unions decided that the Machinists had more resources, more staff, and was in a better position to go after them. Now this is mostly union organizing to some degree, although it’s under a failed procedure. Still, we went after American Racing, and won the election big. As a matter of fact, the Machinists had trouble keeping up with the leadership of these workers.

At American Racing there were labor leaders from Honduras, college educated people from El Salvador and Mexico. They’re doing manual labor, but these were highly educated, highly skilled leadership types. And the Machinists were smart. They gave this local its own number, its own autonomy, and they elected their own leadership. The Machinists amended their constitution to allow for this new immigrant local union. They got a good contract, and now they’re working on their second contract; it’s a good contract.

The American Racing Equipment campaign is about as good a success as you can get under the Board. This was a National Labor Relations Act election. It doesn’t get any better than this. It was the largest single group of workers we organized into the Board in 26 years … In 26 years! And it was a mistake to do it that way. Anybody want to tell me why? Why would I say that the most obvious success in Los Angeles in 26 years was a mistake? It was a mistake because there are nine other wheel factories in Los Angeles with the same conditions and the same kind of workforce.

You see what we did under the Board? There was fire in that plant. There was heat. There was emotion. There was anger. People wanted to change things so bad they organized themselves and went into the street. You know what we did with that anger and that emotion and that momentum and that drive? We circled it and contained it. The steel campaign in the 30s wasn’t about containing the struggle to one company of US Steel in one city in one state. It was about expanding the movement. It was about moving the movement forward.

That’s why American Racing Equipment was wrong. We shouldn’t have contained it under the Board to that one location. Because Olympia Wheel, Western Wheel, and Superior Wheel all had the same conditions. They all had basically the same wages and the same kind of work force. American Racing Equipment wasn’t just a phenomenon that just happened to have labor leaders in its rank-and-file. A lot of these companies had rank-and-file leadership waiting to be tapped. And our job is to provide the climate and the opportunity for them to surface and lead a movement.

Now, the next campaign that was not an NLRB campaign but was about organizing the industry was the drywallers. How many here remember the drywall strike? Yeah, they struck from the Mexican border all the way up to Ventura. In the late 70s this industry paid wages of $10.50 to $12.50 an hour, and they were organized under about three unions. By the time they decided to strike, these people were working 60 hours a week and making $250. No union. No insurance. No benefits. Treated like garbage. What did they have to lose? (See LRR #20.)

I went down to meet with the strikers before adopting their strike. Not picking any one international union but targeting on this group of workers. This is the model some of us have been trying to establish for 15 years. This is the kind of campaign we need in the garment industry. I was the last one to think it would be the drywallers, or that this is where we would establish this kind of structure. We went out and we raised over a million dollars to support the strikers from San Diego to Ventura. They were out for six months, and they organized 75 percent of the drywall industry. Seventy-five percent of that industry is now union again. They’re still not making top wages yet, but they’re on their way now that they’re union.

“Multi-Union Organizing: Speech by David Sickler, December 7, 1995 at UCLA,” Labor Research Review 1:24 (June 1996), 101-110, https://ecommons.cornell.edu/handle/1813/102680.