In the summer of 1992, immigrant construction workers across southern California launched a militant strike that surprised both their employers and the Anglo leaders of trade unions. Aided by the California Immigrant Workers Association (CIWA), the drywallers' strike succeeded in improving working conditions in residential construction across the region. This account is from CIWA organizer Jose De Paz. CIWA operated from 1989-1994 as an associate membership organization of the AFL-CIO.

Three main ingredients account for the success of the drywallers strike. First, the determination of the strikers. They were not doing “strike duty”. They embraced their cause 24 hours a day and everything else became secondary to the strike. Additionally, the strikers were aware that they were being oppressed not only as workers but also as Mexicans, which made their bond twice as strong. This came particularly handy when entire families were evicted from their homes for non-payment of rent and had to move in with one or more families in a single dwelling.

Second, organized labor’s considerable contribution to the independent drywall strike fund. In addition to individuals and community organizations, more than 21 AFL-CIO affiliated unions and six Central Labor Councils in California made significant donations to the fund.

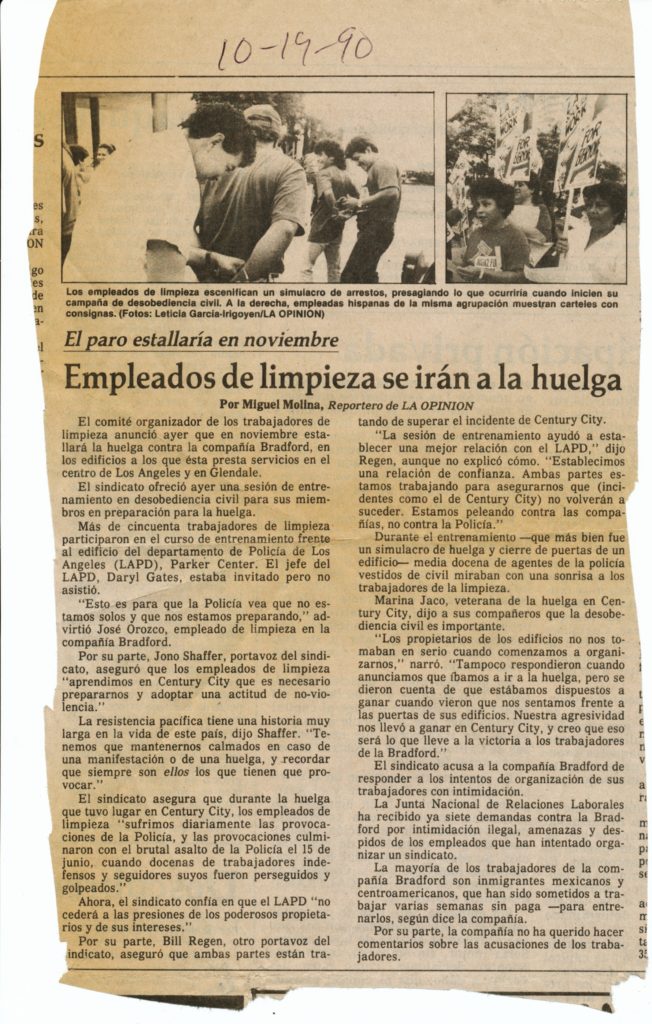

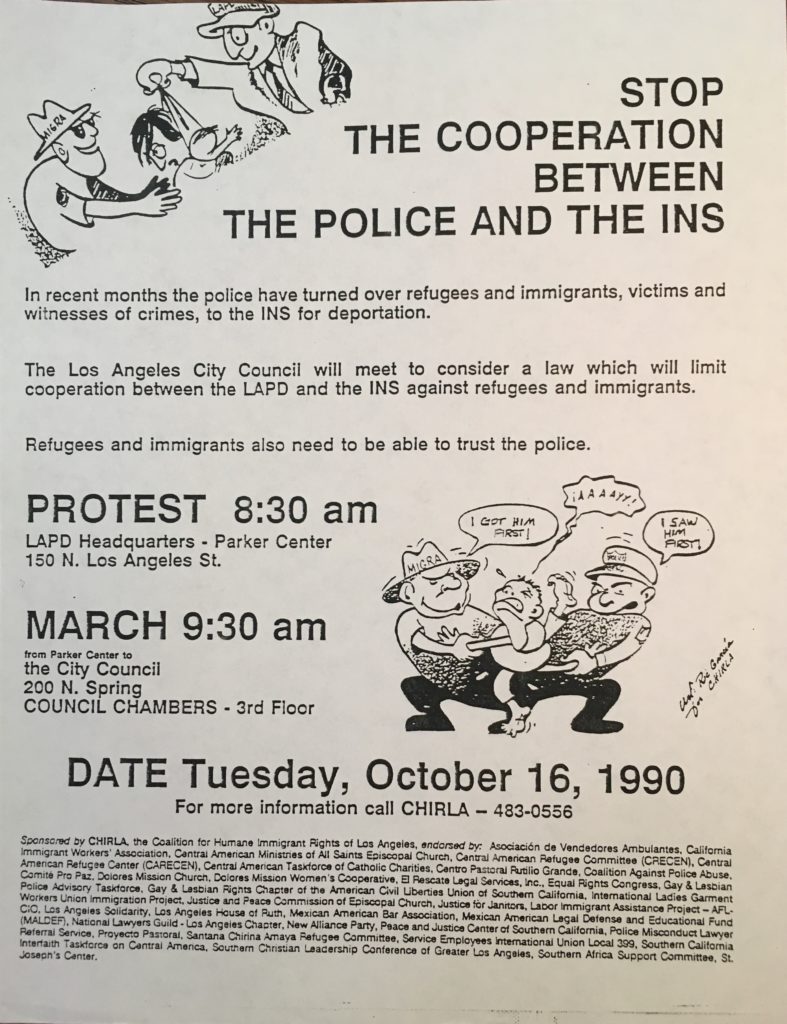

Third, CIWA’s unique participation. Besides coordinating legal and immigration defense, CIWA served as a communication bridge between the strikers and police agencies. CIWA also functioned as the strikers’ spokesperson with the media (particularly the Spanish-language media) and as the coordinator of support from Latino community and labor organizations. CIWA’s unique com bination of skills and its dual credentials in the labor and Latino communities enabled it to convert the drywallers’ struggle from a localized labor dispute into a Latino workers movement.

Continue reading ““They embraced their cause 24 hours a day””