The Living Wage was the first major campaign of LAANE (Los Angeles Alliance for the New Economy, then known at the Tourism Industry Development Council), who helped to conceive of and craft the ordinance in close collaboration with HERE Local 11 (representing hospitality workers) and SEIU Local 399 (representing building services workers). To ensure its passage, they engaged local religious leaders inspiring the creation of CLUE, Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice. Many of CLUE’s founding members had been intimately involved in community organizing before—including civil rights activism, supporting central American refugees, opposition to nuclear arms, and Middle East peace—and wanted to build a new movement for economic justice rooted in theological values.

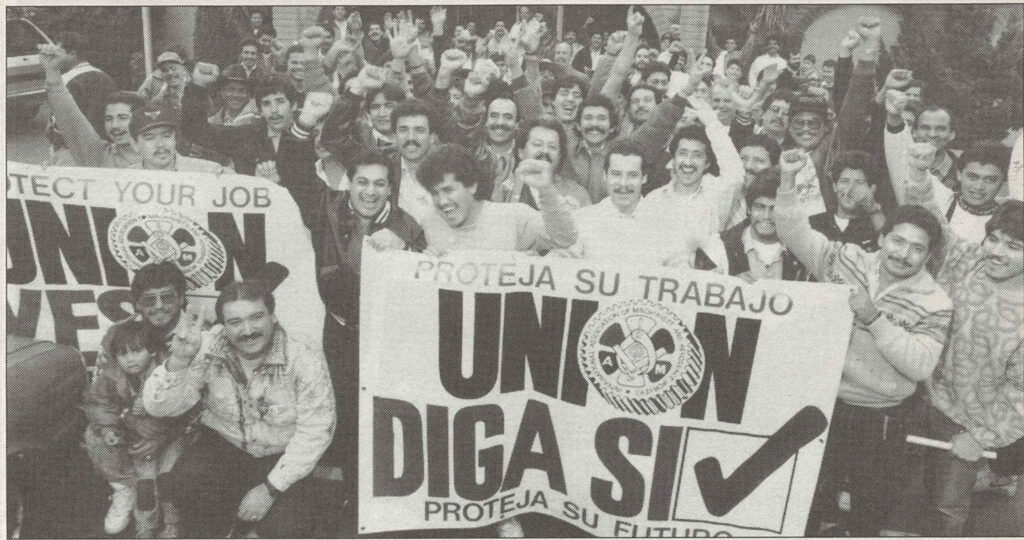

While CLUE’s members came from a variety of faith traditions, its model was based on the Quaker principle of accompaniment, a process of deep relationship building in which religious leaders spent time with workers to learn about their communities’ needs and brainstormed actions and strategies together and then accompanied those workers in supportive roles that would help move their campaigns forward. This photograph, taken by Lotz in 1996, provides an example of that accompaniment in practice. It depicts Rev. Richard Gillett (center back) and Rev. James Lawson Jr. (to his right), both founding members of CLUE standing with a group of workers outside of Los Angeles City Hall as they prepare to visit various City Council offices to encourage members to vote yes on the Living Wage Ordinance. The photo was one of 10 of Lotz’ photographs featured in an exhibition called “Faith at Work,” which was shown at several congregations and community spaces in Southern California before Lotz left Los Angeles to join the staff of the American Friends Service Committee International Programs in 1999.

Borsch, Frederick H, Beerman, Leonard, and Sano Roy, “Yes: It Makes Ethical and Economic Sense,” Los Angeles Times 30 Dec 1996: VCB11. https://www.proquest.com/hnplatimes1/historical-newspapers/yes-makes-ethical-economic-sense/docview/2047937342/sem-2?accountid=14512

View more photos from the Living Wage Campaign: https://www.flickr.com/photos/uclairle/albums/72177720320809410/

View more photos from the Linda A. Lotz Photo Collection: https://www.flickr.com/photos/uclairle/albums/72177720320845755/