The Los Angeles Living Wage Coalition explains the fight to extend the city’s living wage ordinance to workers at Los Angeles International Airport (LAX). This 1998 production features interviews with Madeline Janis-Aparicio (LAANE) and Jackie Goldberg (L.A. City Counsel) as well as scenes of Mike Garcia leading a protest by SEIU Local 1877 at LAX. Rank-and-file workers explain the struggle of living in L.A. while earning low wages.

Miguel Contreras: Warrior for Working Families

As leader of the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor, Miguel Contreras (1952-2005) reshaped LA’s unions into a powerful political, economic, and social force. The child of farm workers, Contreras was an organizer for the United Farm Workers union (UFW), and later the Hotel and Restaurant Employees union (HERE). He led the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor from 1996 until is death in 2005. The LA Alliance for a New Economy produced this video documenting Contreras’s life story and his impact on the city’s labor movement and working people.

Hold the Line Caravan

As the Living Wage Coalition expanded its outreach, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors announced plans to restrict eligibility to, and cut benefits for, its General Relief (or “welfare”) program in accordance with the passage of the federal Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act (better known as “welfare reform”) of 1996. Coalition members, including CLUE (Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice), the Community Coalition, the Coalition to End Hunger and Homelessness, and ACORN (the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now), quickly mobilized to prevent cuts in services that would impact thousands of county residents. In early 1997, they organized a community meeting in which individuals gave testimony and called on Los Angeles County administrators to adopt policies that would protect, rather than restrict, access to social services for those in need. Hundreds of people joined a “Hold the Line Caravan” rally organized by the Los Angeles Coalition to End Hunger and Homelessness in 1997 outside of the meeting to show their support.

Pictured here is Rev. James Lawson Jr. speaking at the “Hold the Line Caravan” rally on behalf of CLUE, as photographed by CLUE’s interfaith organizer Linda A. Lotz. The photograph was featured in an exhibition called “Faith at Work,” which was shown at several congregations and community spaces in Southern California before Lotz left Los Angeles to join the staff of the American Friends Service Committee International Programs in 1999.

Josh Meyer, “County May Slash General Relief: Welfare: Supervisors will vote next week on restricting eligibility and limiting benefits to four months for able-bodied, officials say,” Los Angeles Times May 17, 1997 https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/county-may-slash-general-relief/docview/2110418912/se-2?accountid=14512

View more photos from the Living Wage Campaign: https://www.flickr.com/photos/uclairle/albums/72177720320809410/

View more photos from the Linda A. Lotz Photo Collection: https://www.flickr.com/photos/uclairle/albums/72177720320845755/

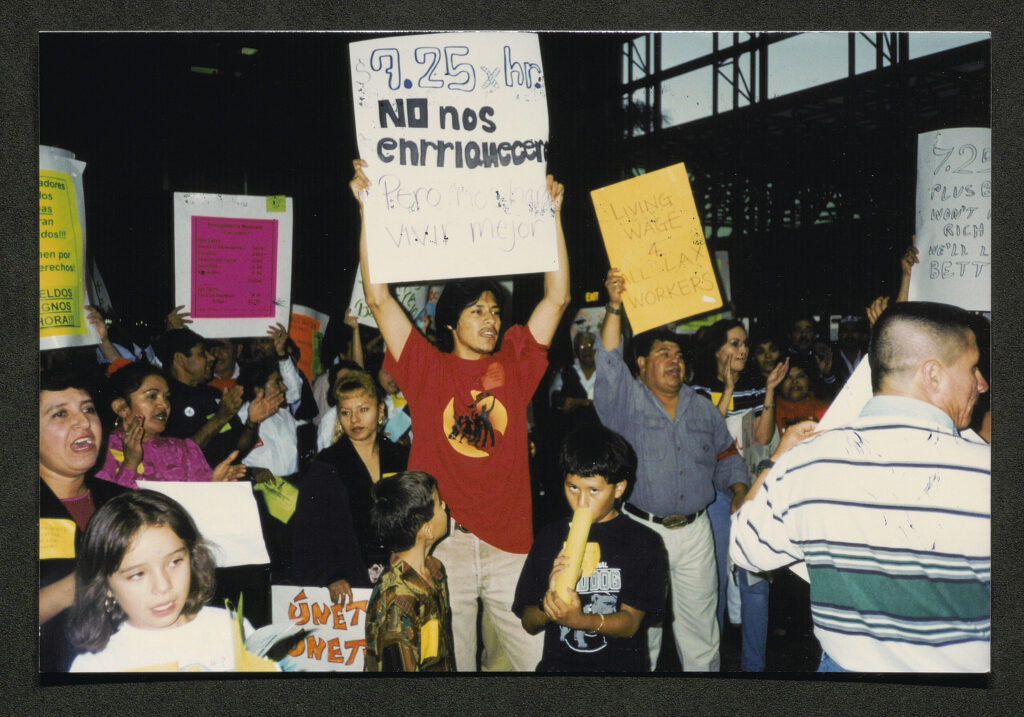

Expanding the Living Wage at LAX

As written, the Los Angeles Living Wage Ordinance only applied to large companies with contracts with the Los Angeles city government, exempting some 2000-3000 low-wage workers at the Los Angeles INternational Airport (LAX), including baggage handlers, wheelchair runners, security officers, and janitorial staff. Their exclusion from the ordinance was based on a legal technicality: while the airlines at LAX maintained contracts with the City of Los Angeles in the form of leases, thanks to a change in city policies, most services at the airport were provided by companies subcontracted by the airlines, which meant that the Living Wage Ordinance did not apply to them. The change in employment relations at LAX meant that jobs once filled by unionized workers employed directly by the airlines became low-wage subcontracted ones, with LAX workers paid wages of as little as $5.15 per hour and with no sick days, holidays, or health benefits. Mayor Richard Riordan, who had initiated the changes that enabled the subcontracting schemes at the airport, made clear his intentions to prevent the ordinance’s expansion at LAX.

SEIU Local 399, representing building trades workers in Los Angeles, had been working to unionize the subcontracted LAX workers for several years before the Living Wage campaign began. When it became clear that airport subcontractors would not abide by the new standards, Local 399 worked with other members of the Living Wage Coalition to organize massive demonstrations at the airport, including this one in October 1997. After months of pressure, the Los Angeles’ Bureau of Contract Administration ruled that the ordinance did apply to the airlines and their subcontractors, but the airlines still refused to comply. Just a few days later, 450 workers at LAX announced their intention to unionize with Local 399.

JIM NEWTON, “Mayor Trying to Keep LAX Exempt From New Pay Law,” Los Angeles Times, Oct. 2, 1997 https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1997-oct-02-mn-38322-story.html

JIM NEWTON, “Agency Says ‘Living Wage’ Law Covers Airport Guards, Janitors; Labor: Ruling is a loss for Riordan, who seeks only voluntary compliance by airlines. Carriers vow to appeal.” Los Angeles Times, June 11, 1998. https://www.proquest.com/latimes/docview/421279834/abstract/D912AFE4172245AEPQ/211

JIM NEWTON, “LAX Security Staff Begins Union Drive; Airport: Workers seek benefits of city’s ‘living wage’ law. They also say employers have threatened retaliation.” Los Angeles Times June 27, 1998. https://www.proquest.com/latimes/docview/421305299/abstract/8DC00FDF184D44F6PQ/1?sourcetype=Newspapers

View more photos from the Living Wage Campaign: https://www.flickr.com/photos/uclairle/albums/72177720320809410/

View more photos from the Linda A. Lotz Photo Collection: https://www.flickr.com/photos/uclairle/albums/72177720320845755/

Holidays Action at City Hall

![a crowd of religious leaders and workers gathered in Los Angeles City hall. On the right, a priest in his white collar and black suit holds a large sign reading "Stop Opposing the Living Wage Ordinance." On the left, a man stands wearing a costume, make up and a wig, posing while reading from a large book in his hands. He is dressed as the ghost of Jacob marley, wrapped in chains. In the background of the image, people hold signs reading "No Trabajo 40 Horas Para Quedarme...[illegible]" "Don't be a Scrooge, work deserves living wages," and other messages.](https://memorywork.irle.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/oversize_001-copy-1024x812.jpeg)

In 1996, as the Los Angeles City Council’s holiday recess approached, members of the Living Wage coalition organized a Christmas-themed action at the last committee hearing on the ordinance. In the preceding weeks, they had sent delegations of workers to council offices and sent heartfelt Thanksgiving messages written by workers and their families to each council member. On the day of the hearing, the Living Wage Coalition planned a theatrical action on the steps outside where staffers dressed as elves and community members carried handmade signs with holiday-themed messages. As Tom Hayden, then a candidate for Mayor of Los Angeles, addressed the crowd, coalition-member Dave Clennon approached dressed head-to-toe in costume as the ghost of Jacob Marley from the Christmas Carol. He continued his slow march into the chamber, first addressing the press, and then the council, in character, warning them not to go the way of Scrooge by opposing the ordinance. The coalition’s efforts were ultimately successful: the ordinance passed a committee vote that day and was eventually voted into law in March 1997.

Pictured here: Clennon reads his address to the press outside of the City Council chambers with a group of workers and community members including (right to left): Reverend Joseph William Frazier, Rev. James Lawson Jr., Tom Hayden (then a candidate for Mayor of Los Angeles), and Epsicopal Bishop Chester Talton. The photo was one of 10 photographs by Linda A. Lotz featured in an exhibition called “Faith at Work” which was shown at several congregations and community spaces in Southern California in 1999.

JEAN MERL, “L.A. Council OKs ‘Living Wage’ Law for City Contracts: Labor: With Enough Votes to Override Promised Riordan Veto, Panel Approves Minimum Pay for Lowest-Level Workers.” Los Angeles Times (1996-Current); Los Angeles, Calif, March 19, 1997, sec. Orange County. https://search.proquest.com/hnplatimes/docview/2109359639/abstract/17BA1ABB1F7142F2PQ/101.

Watch footage of Dan Clennon as Jacob Marley: https://vimeo.com/236469814

View more photos from the Living Wage Campaign: https://www.flickr.com/photos/uclairle/albums/72177720320809410/

View more photos from the Linda A. Lotz Photo Collection: https://www.flickr.com/photos/uclairle/albums/72177720320845755/