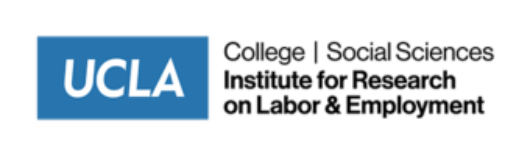

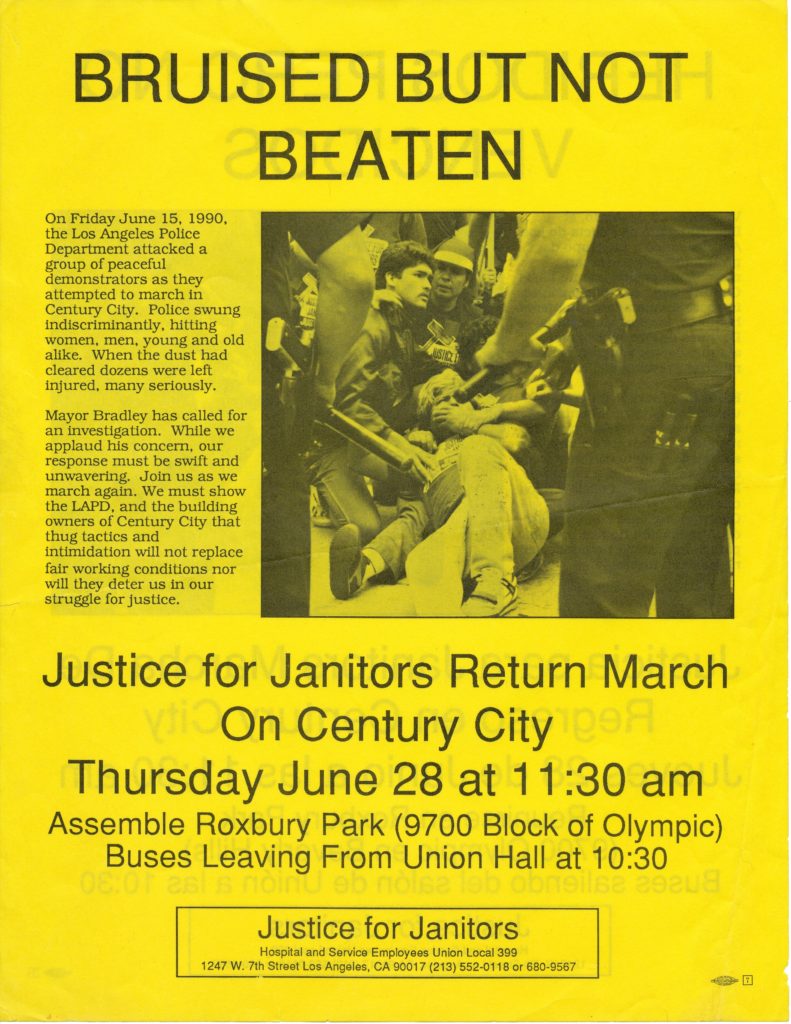

On June 15, 1990, the LAPD armed with nightsticks attacked group of peaceful demonstrators outside Century City that included women and children. Not intimidated by police brutality, the demonstrators continued to protest until fair working conditions were given.

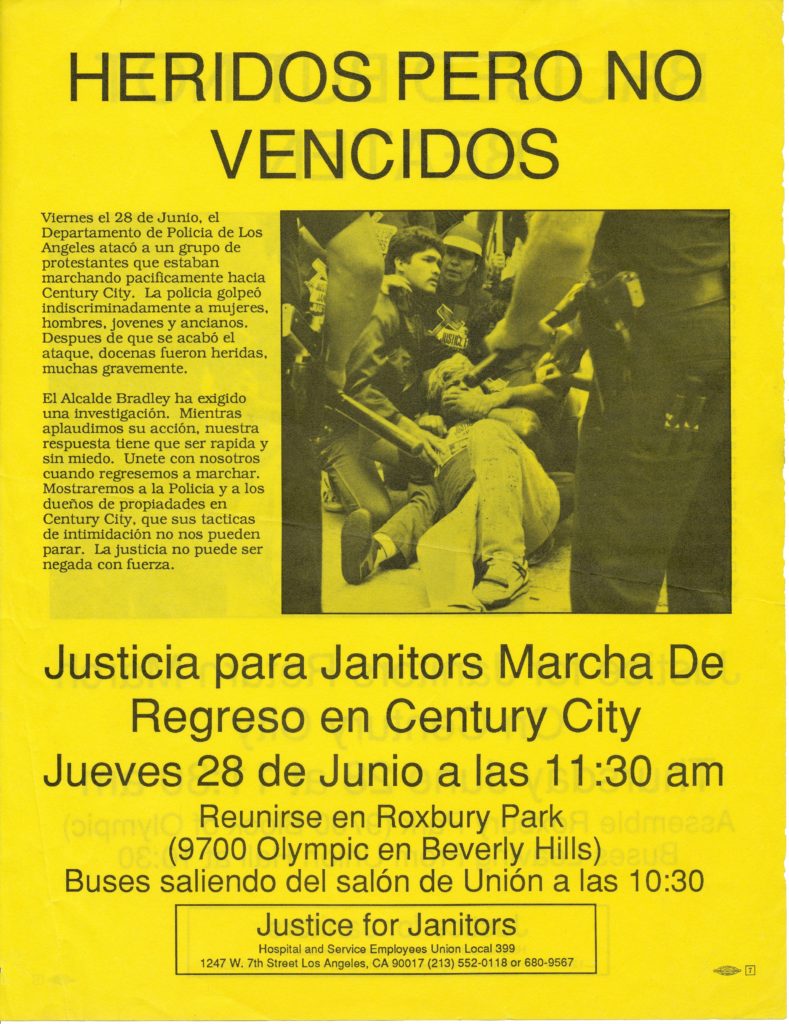

Seguro Medico? Si Se Puede! Mopman y Local 399 Luchando por tus Derechos!

In this cartoon from the Justice for Janitors campaign, two workers worry about the cost of healthcare. The superhero Mopman tells them that having good health insurance is like “having extra money in your pockets.” In cartoons and street theater, the character Mopman was part of the union’s strategy to reach rank-and-file janitors.

Unions review impact of immigration reform

The AFL-CIO published this information for unions and workers in the wake of the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986. The law created a process for many undocumented residents to regularize their status, and the pamphlet highlights organized labor’s role in helping “undocumented workers attain legal status and prevent discrimination by employers.” In Los Angeles, the Labor Immigrant Assistance Project (LIAP) supported workers’ amnesty applications, and the California Immigrant Workers Association (CIWA) served as a general union for immigrant workers without collective bargaining in their workplaces. IRCA also created a new federal prohibition on hiring undocumented workers, something immigrant rights advocates and organized labor in Los Angeles had strongly opposed, but the national AFL-CIO supported. The AFL-CIO abandoned this policy in 2000. View the Document.

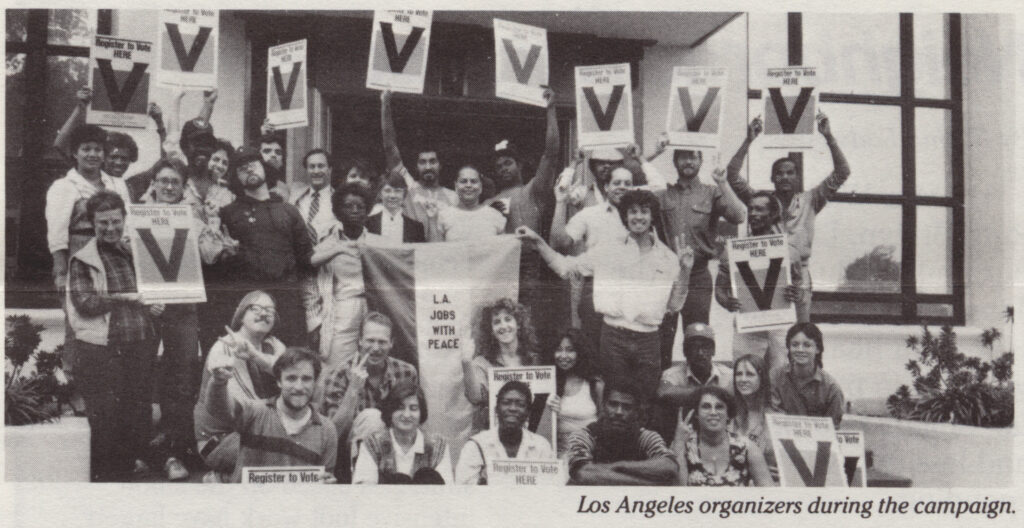

Jobs with Peace

How can progressive political movements win power in geographically expansive and multiracial cities like Los Angeles? The answer, according to the Los Angeles Jobs with Peace campaign was “coalition architecture,” an intentional strategy to link the interests of organized labor with the peace movement, the women’s movement, and the African American civil rights movement through the shared goal of creating good jobs for all by redirecting money from military to domestic spending. In 1984 and 1986, the campaign backed citywide ballot initiatives and built a network of supporters at the precinct level to turnout voters. The 1984 Proposition X called on the city to research and report on pension and contract funds that flowed to military contractors. It passed by a comfortable margin. Proposition V in 1986 would have established a commission to advise the city on how to redirect funds away from military contractors. Proposition V faced a well-funded opposition campaign from business interests and lost by a wide margin. Despite the defeat, the campaign built an effective get-out-the-vote operation at the precinct level that would be the basis of future progressive victories.

Continue reading “Jobs with Peace”Somma waterbed workers win back pay, 1985

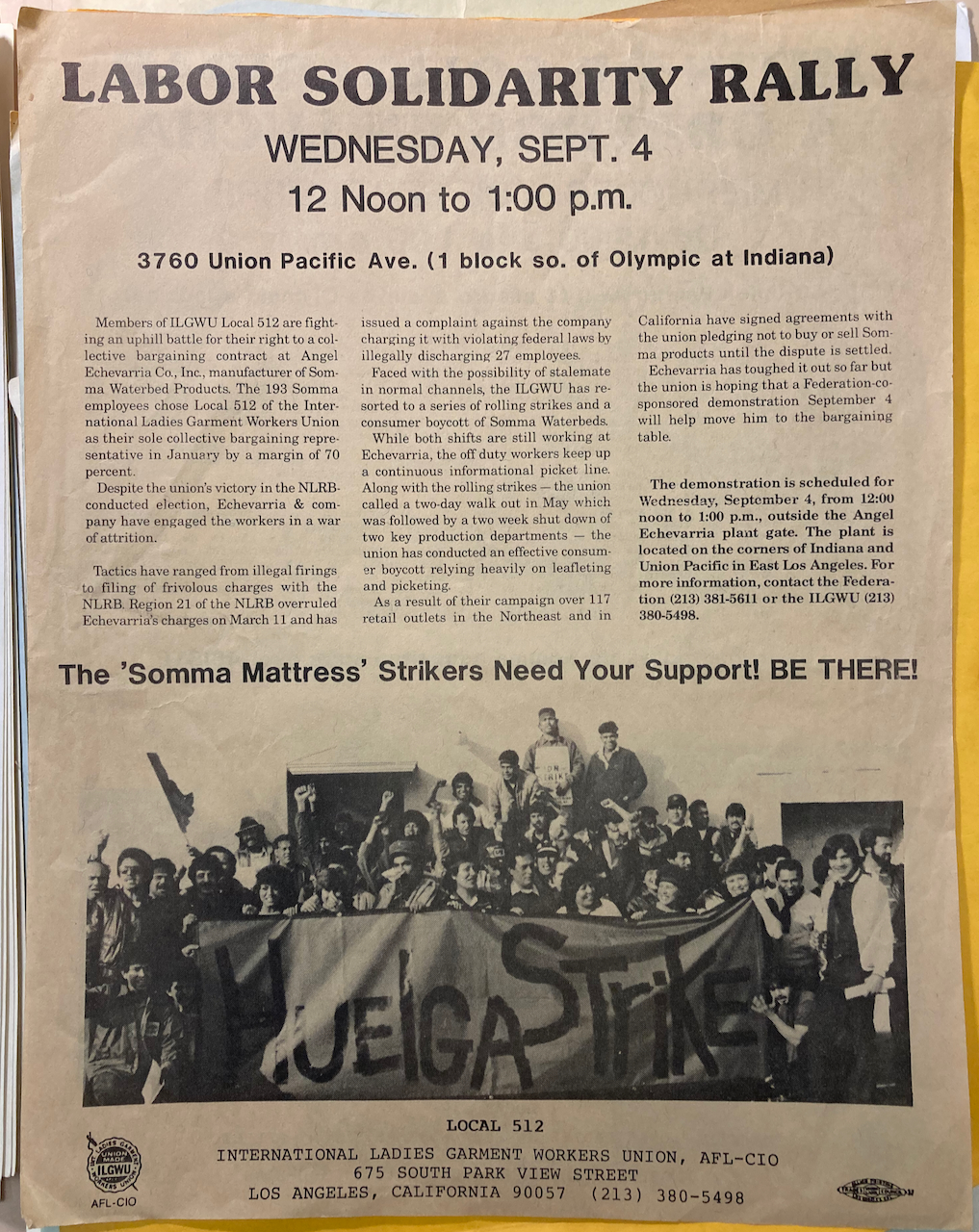

In 1984, workers at the Somma waterbed factory in East Los Angeles began organizing fellow workers at neighborhood soccer games and decide to join the ILGWU. Most of the workers were immigrants from Mexico and Central America, many without documentation. Their employer was Angel Echevarria, a prominent figure in the Latino community and in Los Angeles politics. In January 1985, Somma workers voted 117-48 for a union. The company refused to negotiate with the workers and illegally fired more than 20 key union activists.

The ILGWU and the fired Somma workers held continuous pickets outside the factory, joined by other workers on their lunch breaks and by community supporters. They also launched a boycott of Somma waterbeds to bring their employer to the bargaining table. When the company fired another group of organizers, workers walked out on strike and won their jobs back. After a long delay, the NLRB ordered the fired workers rehired with back pay and upheld the union election over the companies objections.

Sources: ILGWU Photographs, Box 3, Folder 9, Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives at the Cornell University Library. Rosalio Muñoz papers, Box 64, Folder 3, UCLA Library Department of Special Collections.